Understanding Consumer Data Privacy

Data privacy, primarily, is focused on the set boundaries surrounding what personal data is, and what is ideal behavior when processing such. These boundaries typically are set by societal expectations, ethical canons, and legal frameworks that work toward minimizing harm while respecting legitimate uses of this data.

What Counts as Personal Data

Personal data includes any information that can identify an individual directly or indirectly. Obvious examples are names, email addresses, phone numbers, and government-issued identifiers. Less obvious forms include IP addresses, device identifiers, location histories, and behavioral patterns that can be linked back to a person. Even data that appears anonymous may still be personal if it can be re-identified when combined with other datasets.

As technology advances, the scope of personal data continues to expand. Biometric markers, browsing habits, and inferred preferences are increasingly treated as personal information. This broader definition reflects the reality that identity is no longer tied to a single data point but emerges from patterns across many signals.

How Personal Data Is Collected

Personal data is collected through both active and passive means. Active collection happens when individuals fill out forms, create accounts, or provide information directly. Passive collection occurs through cookies, sensors, background analytics, and system logs that operate without explicit interaction. Many digital services rely heavily on this second category.

The challenge with passive collection is visibility. People often do not realize how much data is gathered simply by using a service. This gap between user awareness and system behavior is a key driver of privacy concerns and has shaped calls for clearer disclosure and stronger limits.

Why Context Matters

Data does not exist in isolation. The same piece of information can be harmless in one context and sensitive in another. For example, a location record may be useful for navigation but risky when used to infer personal routines. Consumer data privacy emphasizes the importance of contextual integrity, meaning data should only be used in ways that align with the circumstances in which it was collected.

Respecting context helps prevent misuse and unexpected outcomes. When data is repurposed without regard for original expectations, trust erodes. Context-aware practices are therefore central to responsible data handling.

Where Privacy Risks and Misuse Occur

In many ways, privacy risks crop from the circumstance that data is mishandled-so haphazardly, so indiscriminately, or in a deceitful manner. Such hazards do not merely result from assaults on one's privacy. Too many privacy breaches arise from through botched system design, poorly articulated policies, and the incentives that outweigh the drawbacks of restricting the surfeit of data accumulation. So, from where is the misuse found? This question serves to answer partly why privacy protections are deemed necessary.

Misuse might be the result of different human actions-ranging from sharing data with unauthorized persons or companies to the excessive collection and purposeless retention of the data. Each of these actions undermines the individual in different respects-that is to say, in incidents involving financial loss, discrimination, and the loss of autonomy over one's personal data. This section provides a few such risk categories and the likely far-reaching outcomes of their deployment.

Overcollection and Excessive Retention

One of the most common privacy issues is collecting more data than necessary. Organizations may gather information “just in case” it becomes useful later. This practice increases exposure without providing immediate benefit to the consumer. The longer data is stored, the greater the risk of misuse or breach.

Excessive retention also undermines accountability. Data kept indefinitely is harder to manage, audit, or secure. Privacy-focused approaches encourage minimizing both the amount of data collected and the duration it is stored.

Secondary Use Without Clear Permission

Secondary use occurs when data collected for one purpose is later used for another. This might include marketing, profiling, or sharing with third parties. Problems arise when these new uses were not clearly disclosed or reasonably expected at the time of collection.

Consumers often have little visibility into secondary uses, making it difficult to assess risks or exercise control. Transparency and consent mechanisms aim to address this gap, but they are only effective if designed with clarity and restraint.

Security Failures and Unauthorized Access

Even when data is collected and used responsibly, weak security can expose it to unauthorized access. Breaches may result from technical vulnerabilities, human error, or inadequate safeguards. The impact on individuals can be severe, ranging from identity theft to long-term reputational harm.

Security is therefore inseparable from privacy. Protecting data requires not only ethical intent but also ongoing investment in technical and organizational controls that evolve alongside threats.

Opaque Systems and Lack of Oversight

Complex data systems often operate behind the scenes, making it hard for consumers to understand how decisions are made. Automated profiling and algorithmic processing can amplify this opacity. When individuals cannot see or challenge how their data is used, accountability weakens.

Consumer data privacy seeks to counter this by promoting explainability and oversight. Systems should be understandable enough to allow meaningful review, even if their inner workings are technically complex.

Core Principles of Consumer Data Privacy

Modern privacy thinking is guided by a set of core principles that shape laws, policies, and best practices. These principles provide a framework for evaluating data practices and identifying responsible behavior. They are not rigid rules but shared reference points that adapt across contexts.

By focusing on principles rather than specific technologies, consumer data privacy remains relevant as systems evolve. The following subsections outline the most widely accepted foundations of privacy-oriented data handling.

Purpose Limitation and Data Minimization

Purpose limitation means only collecting data for specific, verifiable purposes and not for use outside of those purposes. Data minimization is a complementary concept whereby business industries are urged to collect only the necessary. This set of principles works to reduce the over-exposure of information winter and thereby greatly limit misuse.

When implemented consistently, these principles serve to shift the modeling of data collection from accumulating data to responsible stewardship. Such a shift brings an organization's practices in line with the real consumer expectations, along with their desire to build long-term credibility.

Transparency and Clarity

Transparency requires that data practices be explained in clear, accessible terms. Consumers should know what data is collected, why it is needed, and how it will be used or shared. Vague or overly technical disclosures undermine this goal.

Clarity also involves timing. Information should be provided when it is most relevant, not buried in lengthy documents that few people read. Effective transparency supports informed decision-making rather than formal compliance alone.

Consent and Choice

Consent is a cornerstone of consumer data privacy, but its quality matters. Meaningful consent is informed, specific, and freely given. It should not be coerced through unnecessary requirements or bundled with unrelated services.

Choice extends beyond initial consent. Consumers should be able to change their preferences, withdraw permission, and access alternatives where possible. These mechanisms reinforce the idea that data sharing is a relationship, not a one-time transaction.

Accountability and Responsibility

Accountability places responsibility on organizations to uphold privacy commitments and demonstrate compliance. This includes internal governance, regular assessments, and clear lines of ownership for data practices.

Accountability also means responding effectively when things go wrong. Acknowledging failures, correcting issues, and mitigating harm are essential to maintaining credibility and protecting consumers.

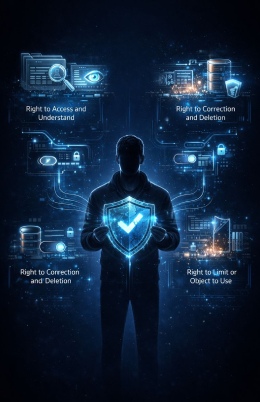

Consumer Rights in Data Privacy

Consumer data privacy is not only about organizational behavior. It also defines rights that individuals can exercise in relation to their personal information. These rights empower consumers to participate actively in data governance rather than remaining passive subjects.

While the specific scope of rights varies across jurisdictions, common themes have emerged globally. Understanding these rights helps individuals recognize what they can reasonably expect from data-driven systems.

The Right to Access and Understand

Consumers increasingly have the right to know what data is held about them and how it is used. Access rights allow individuals to request copies of their personal data and obtain explanations of processing activities.

This right supports transparency and accountability. It also enables consumers to identify inaccuracies or practices they may wish to challenge or change.

The Right to Correction and Deletion

Errors in personal data can have real consequences. Correction rights allow individuals to update inaccurate or incomplete information. Deletion rights, often called the right to be forgotten, enable consumers to request removal of data under certain conditions.

These rights acknowledge that data should not outlive its relevance or accuracy. They reinforce the idea that personal information remains connected to the individual, even after collection.

The Right to Limit or Object to Use

Beyond access and deletion, consumers may have the right to restrict how their data is used. This includes objecting to certain processing activities or requesting temporary limits while disputes are resolved.

Such rights provide flexibility and protection in situations where outright deletion is not appropriate. They help balance individual interests with legitimate organizational needs.

Organizational Responsibilities and Practical Safeguards

Organizations play a central role in protecting consumer data privacy. Their responsibilities extend beyond legal compliance to include ethical judgment and system design choices. Embedding privacy into everyday operations reduces risk and builds trust over time.

This section outlines key responsibilities and includes a focused list of practical safeguards that support responsible data handling.

Designing Privacy Into Systems

The concept of privacy-by-design is about data protection from the inception stages of development of any system. Instead of considering privacy as an add-on, it is made an integral part, akin to capability and performance. This competes with the thoughtful default settings and restricts data fairness restrictions-think of how naïve data handling favoring the individual can be. Consequently, it reduces the practice of hastily rectifying the same fault time and again and poor measures.

- Collecting data for specific purposes only

- Controlling access based on necessity

- Using aggregation or anonymization when the technology permits it

- Having set retention schedules and deletion purposes

Internal Governance and Training

Strong governance structures ensure that privacy responsibilities are understood and enforced internally. This includes assigning clear ownership, documenting processes, and providing regular training to staff who handle personal data.

Training helps translate abstract principles into everyday decisions. When employees understand the impact of their actions, digital privacy becomes part of organizational culture rather than a compliance checkbox.

Privacy as Shared Stewardship

Consumer data privacy is not a one-time policy but an ongoing practice, occasioned by the understanding that personal data comes with a set of values, risks, and duties. Collective participation implies that all individuals, organizations, and institutions play a part in determining data's treatment.

#InternationalDataPrivacyDay

— All India Radio News (@airnewsalerts) January 28, 2026

🔹International Data Privacy Day is being observed today to raise awareness about protecting personal data and privacy in the digital age.

🔹Also known as #DataProtectionDay, it was designated in 2006 by the Council of Europe to mark the signing of… pic.twitter.com/Bv1aB7i4NO